2021 Summer Heatwaves: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

=== June Heat Dome in Portland (OERS 2021-1650) === | === June Heat Dome in Portland (OERS 2021-1650) === | ||

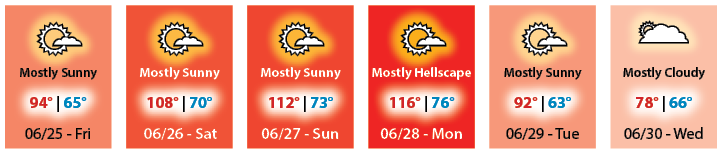

From June 25 to 29, a heat dome parked itself over the Portland metropolitan area and obliterated temperature records all over the Pacific Northwest. Portland experienced three consecutive days of abnormally high heat reaching 108, 112, and 116 degrees. Dr. Vivek Shandas with Portland State University recorded a sidewalk surface temperature at SE Woodstock and 92nd Avenue that hit 180 degrees, high enough for third degree burns at direct skin contact.<ref>Peel, Sophie. “This Is the Hottest Place in Portland.” Willamette Week, https://www.wweek.com/news/city/2021/07/14/this-is-the-hottest-place-in-portland/. </ref> | From June 25 to 29, a heat dome parked itself over the Portland metropolitan area and obliterated temperature records all over the Pacific Northwest. Portland experienced three consecutive days of abnormally high heat reaching 108, 112, and 116 degrees. [https://www.pdx.edu/profile/vivek-shandas Dr. Vivek Shandas] with Portland State University recorded a sidewalk surface temperature at SE Woodstock and 92nd Avenue that hit 180 degrees, high enough for third degree burns at direct skin contact.<ref>Peel, Sophie. “This Is the Hottest Place in Portland.” Willamette Week, https://www.wweek.com/news/city/2021/07/14/this-is-the-hottest-place-in-portland/. </ref> | ||

As of December 1, 2021, the County Medical Examiner confirmed 73 heat related deaths in Multnomah County from the June heatwave. Previously, between 2010 and June 2021, Multnomah County ever recorded only two heat illness (hyperthermia) deaths.<ref>''Ibid.''</ref> Combining the 73 with deaths elsewhere in Oregon, Washington, Idaho and British Columbia, the heat dome led to the deaths of approximately 500 people. Most of the persons who died were older, white, and socially isolated or lived alone and without central air conditioning. Their deaths were preventable. | As of December 1, 2021, the County Medical Examiner confirmed 73 heat related deaths in Multnomah County from the June heatwave. Previously, between 2010 and June 2021, Multnomah County ever recorded only two heat illness (hyperthermia) deaths.<ref>''Ibid.''</ref> Combining the 73 with deaths elsewhere in Oregon, Washington, Idaho and British Columbia, the heat dome led to the deaths of approximately 500 people. Most of the persons who died were older, white, and socially isolated or lived alone and without central air conditioning. Their deaths were preventable. | ||

[[File:Heatwave.png|alt=June heatwave dates and temperatures.|center | [[File:Heatwave.png|alt=June heatwave dates and temperatures.|center|''June heatwave dates and temperatures.''|frame]]Emergency managers in the region mobilized for heatwave preparations only three days before June 25. Since more preparation lead time can improve response capacity, it is worth noting factors that possibly contributed to curtailed lead time in June: | ||

* '''Regional response inexperience with temperature extremes at this level.''' For example, at the time, PBEM did not have Operational Guidelines in place for an event like the June heat dome. | |||

* '''Conservative weather forecasts leading up to the heat event.''' A June 21 NWS weather briefing indicated a high confidence forecast of temperatures above 90° starting June 25 with a 50% chance of temperatures hitting 100° that weekend. Concerning, but not highly alarming. Email traffic at PBEM confirms professionals in the region took the prospective heat seriously and worked to plan for it; but until June 22, some doubts remained Portland would reach temperatures over 100° that weekend. Solid indications from NWS that temperatures would exceed 100° on Sunday and Monday in addition to Friday and Saturday do not appear in email traffic until the morning of June 23. Even on the days that followed, the forecasted hottest day and temperatures changed. | |||

* '''A community safety net already stretched and frayed by COVID-19.''' The pandemic has led to increased social isolation (a factor in heat illness deaths) and houselessness. | |||

* '''A possible boil water notice looming over much of the west coast.''' Regional emergency managers were planning for a prospective interruption of the supply of sodium hypochlorite.<ref>Hasenstab, A. (2021, July 6). Chlorine shortage comes to an end in Portland as production ramps up. Oregon Public Broadcasting. Retrieved January 8, 2022, from https://www.opb.org/article/2021/07/06/oregon-chlorine-shortage-portland-water-bureau-washington-chemical-facility/</ref> Utilities use sodium hypochlorite to disinfect drinking water and wastewater. An equipment failure at a chlorine manufacturer in Longview resulted in a shortage of the disinfectant impacting the entire west coast. From June 14 to 28, utilities and emergency managers braced for the possibility of running out. That did not happen. But the implications of a short chlorine supply were serious: it could mean asking Portlanders to curtail water use and possibly a regional boil water notice. This incident held the attention and resources of emergency managers right up to the June heatwave. | |||

In other words, the June heat dome was a growing emergency inside [[wikipedia:Matryoshka_doll|matryoshka dolls]] of emergencies. | |||

PBEM moved the ECC into partial activation on June 23. That day, the COAD Coordinator began mobilizing community outreach efforts via PDX COAD on June 23, sending warnings and instructions to partner CBOs and calling some of them individually to check in. In a meeting the next day, Multnomah County decided to open two cooling centers beginning on Friday, June 25: the Oregon Convention Center and Sunrise Center (and later added the Arbor Lodge Shelter). A bulletin to NETs that day put them on standby for volunteering, but online shift signups were not available for sending to NETs until 11:00 the next day (June 24). Multnomah County Emergency Management took responsibility for the online signups, but posted eight hour shifts instead of the four hour shifts customarily offered to volunteers. The short notice combined with the long shifts later factored into low volunteer availability. On June 25, Portland’s Chief Administrator’s Office requested help from City employees to fill shift gaps. | |||

Throughout the heatwave, staffing needs at cooling centers changed as the City and County expanded cooling center operating hours. The shift additions, though essential, necessitated repeated requests to volunteers for staffing many times in the midst of the emergency. | |||

On June 24, Multnomah County requested assistance from the City reaching out to residents at apartment buildings by phone; Maybelle Center for Community made a similar request the same day to the COAD Coordinator. NET Coordinators posted an electronic signup to recruit phone welfare check volunteers late the following evening. | |||

Portland NET and COAD responded throughout the heatwave, and through the demobilization of cooling centers on July 2. | |||

== Notes and References == | == Notes and References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 00:04, 26 November 2022

This page under construction

SUMMARY HERE

This after action report (AAR) focuses on the response of Portland’s Neighborhood Emergency Team (“NET”)volunteers and community organizations in the Portland Community Organizations Active in Disaster network (“PDX COAD”). The primary audience for this AAR includes NET volunteers, NET Team Leaders, PBEM Program Managers, and COAD member organizations.

AAR Definitions and Acronyms

In addition to the usual complement of government acronyms, we present a few important distinctions between cooling facilities:[1]

- Cooling Center: A type of Disaster Resource Center with air conditioning, cooling resources, water, food, and support services. These locations operate during the hottest part of the day only.

- Cooling Shelter: A type of Disaster Resource Center with air conditioning, cooling resources, water, food, and support services. These locations are similar to Cooling Centers, but operate for 24-hours. This resource is particularly important when overnight temperatures do not allow people to cool down enough.

- Cooling Space: An air-conditioned space open to the public with water often available. These spaces are open during the hottest part of the day only and do not operate for 24 hours. Community partners, such as houses of worship, may operate Cooling Spaces. Multnomah County libraries also served as cooling spaces.

- Cooling Resources: Items like water, cooling towels, electrolytes, misters and fans, and supports such as transportation to Cooling Shelters and Centers to help someone get cool or stay cool.

Other key terms used in this AA include:

- CBOs: Community Based Organizations; usually mentioned in the context of the COAD.

- COAD (or PDX COAD): Community Organizations Active in Disaster. A network of community and faith based organizations that address disaster preparedness, response, and recovery.

- IAP: Incident Action Plan. A documented response strategy to an emergency incident.

- JOHS: Joint Office of Homeless Services, the lead local government agency for addressing homelessness.

- JVIC: A network of CBOs separate from the COAD, but mobilized during the COVID response.

- NET: Portland Neighborhood Emergency Teams.

- NWS: National Weather Service.

- PBEM: Portland Bureau of Emergency Management.

- SUV: Spontaneous unaffiliated volunteer; often used when describing emergent volunteers from the general public.

Background and Timeline

Assets and Capabilities

Portland Neighborhood Emergency Teams (Portland NET)

Portland NET is the largest volunteer Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) program by membership in the Portland Metro Area, with 2,105 active volunteers and over 29,000 volunteer hours contributed in 2020. The Portland Bureau of Emergency Management (PBEM) manages NET, with selected PBEM staff assigned to oversee NET deployments. PBEM and NET aim to serve the community with a trauma informed perspective and lead responses with equity and inclusion first.

The depth of Portland NET’s bench of volunteers is key to its operational capacity. Not only does having a large pool of volunteers to draw from mean that NET can fill hundreds of volunteer shifts in a deployment (including overnight shifts), but also provide the deployment with a diversity of relevant expertise. For example, volunteer skill and knowledge of disaster psychology, public outreach, administration, and mental health crisis de-escalation all played critical roles in inclement weather response. For example, in one cooling center deployment, the specific help of Spanish-speaking volunteers with de-escalation training was needed.

Portland Communities Active in Disaster (PDX COAD)

PDX COAD is a relatively new and growing PBEM program. The COAD constitutes a PBEM-faciliated network of local community and faith based organizations (CBOs). The PBEM COAD Coordinator provides disaster preparation information and supports CBOs in disaster response roles and operations. At the time of the June heatwave, the COAD consisted of around 60 organizations.

The COAD Coordinator relayed important heat illness prevention information to the CBOs to pass on to their constituencies. Several CBOs also volunteered to take a response role by opening their own neighborhood-local cooling centers.

June Heat Dome in Portland (OERS 2021-1650)

From June 25 to 29, a heat dome parked itself over the Portland metropolitan area and obliterated temperature records all over the Pacific Northwest. Portland experienced three consecutive days of abnormally high heat reaching 108, 112, and 116 degrees. Dr. Vivek Shandas with Portland State University recorded a sidewalk surface temperature at SE Woodstock and 92nd Avenue that hit 180 degrees, high enough for third degree burns at direct skin contact.[2]

As of December 1, 2021, the County Medical Examiner confirmed 73 heat related deaths in Multnomah County from the June heatwave. Previously, between 2010 and June 2021, Multnomah County ever recorded only two heat illness (hyperthermia) deaths.[3] Combining the 73 with deaths elsewhere in Oregon, Washington, Idaho and British Columbia, the heat dome led to the deaths of approximately 500 people. Most of the persons who died were older, white, and socially isolated or lived alone and without central air conditioning. Their deaths were preventable.

Emergency managers in the region mobilized for heatwave preparations only three days before June 25. Since more preparation lead time can improve response capacity, it is worth noting factors that possibly contributed to curtailed lead time in June:

- Regional response inexperience with temperature extremes at this level. For example, at the time, PBEM did not have Operational Guidelines in place for an event like the June heat dome.

- Conservative weather forecasts leading up to the heat event. A June 21 NWS weather briefing indicated a high confidence forecast of temperatures above 90° starting June 25 with a 50% chance of temperatures hitting 100° that weekend. Concerning, but not highly alarming. Email traffic at PBEM confirms professionals in the region took the prospective heat seriously and worked to plan for it; but until June 22, some doubts remained Portland would reach temperatures over 100° that weekend. Solid indications from NWS that temperatures would exceed 100° on Sunday and Monday in addition to Friday and Saturday do not appear in email traffic until the morning of June 23. Even on the days that followed, the forecasted hottest day and temperatures changed.

- A community safety net already stretched and frayed by COVID-19. The pandemic has led to increased social isolation (a factor in heat illness deaths) and houselessness.

- A possible boil water notice looming over much of the west coast. Regional emergency managers were planning for a prospective interruption of the supply of sodium hypochlorite.[4] Utilities use sodium hypochlorite to disinfect drinking water and wastewater. An equipment failure at a chlorine manufacturer in Longview resulted in a shortage of the disinfectant impacting the entire west coast. From June 14 to 28, utilities and emergency managers braced for the possibility of running out. That did not happen. But the implications of a short chlorine supply were serious: it could mean asking Portlanders to curtail water use and possibly a regional boil water notice. This incident held the attention and resources of emergency managers right up to the June heatwave.

In other words, the June heat dome was a growing emergency inside matryoshka dolls of emergencies.

PBEM moved the ECC into partial activation on June 23. That day, the COAD Coordinator began mobilizing community outreach efforts via PDX COAD on June 23, sending warnings and instructions to partner CBOs and calling some of them individually to check in. In a meeting the next day, Multnomah County decided to open two cooling centers beginning on Friday, June 25: the Oregon Convention Center and Sunrise Center (and later added the Arbor Lodge Shelter). A bulletin to NETs that day put them on standby for volunteering, but online shift signups were not available for sending to NETs until 11:00 the next day (June 24). Multnomah County Emergency Management took responsibility for the online signups, but posted eight hour shifts instead of the four hour shifts customarily offered to volunteers. The short notice combined with the long shifts later factored into low volunteer availability. On June 25, Portland’s Chief Administrator’s Office requested help from City employees to fill shift gaps.

Throughout the heatwave, staffing needs at cooling centers changed as the City and County expanded cooling center operating hours. The shift additions, though essential, necessitated repeated requests to volunteers for staffing many times in the midst of the emergency.

On June 24, Multnomah County requested assistance from the City reaching out to residents at apartment buildings by phone; Maybelle Center for Community made a similar request the same day to the COAD Coordinator. NET Coordinators posted an electronic signup to recruit phone welfare check volunteers late the following evening.

Portland NET and COAD responded throughout the heatwave, and through the demobilization of cooling centers on July 2.

Notes and References

- ↑ Multnomah Cunty. (2021, August 18). June 2021 Extreme Heat Event: Preliminary Findings and Action Steps. https://multco-web7-psh-files-usw2.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/June2021_Heat_Event-Preliminary_Findings-08_21%20%281%29.pdf

- ↑ Peel, Sophie. “This Is the Hottest Place in Portland.” Willamette Week, https://www.wweek.com/news/city/2021/07/14/this-is-the-hottest-place-in-portland/.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Hasenstab, A. (2021, July 6). Chlorine shortage comes to an end in Portland as production ramps up. Oregon Public Broadcasting. Retrieved January 8, 2022, from https://www.opb.org/article/2021/07/06/oregon-chlorine-shortage-portland-water-bureau-washington-chemical-facility/